I’m a Human Risk Manager (I Think?)

Jun 03

Experience OutThink

If you’re keeping any sort of eye on the bit of security where we look at how humans behave, you can’t help but think we're having a bit of an identity crisis. We used to be called Security Awareness, and that was fine, but then people started saying, “Well, awareness isn’t enough! We need to do more!” We then witnessed the rise of Human Behavior and Security Culture - all good things, and important. But none of those names really seemed to stick.

And now (as if we needed yet more terminology), we’ve started talking about Human Risk. More specifically, how professionals are now Human Risk Managers, not Security Awareness Officers. Human Risk was more dynamic, more powerful … in many ways more accurate. And that was it. We’re now decided. We are all Human Risk Managers.

Except.

There’s always an except, isn’t there?

Except, some people don’t like it. Why? Let’s start with some history.

History Lesson: On the Naming of Names

Way back towards the end of the last millennium (1996, if we’re going to be precise) the venerable National Institute for Science and Technology issued a Special Paper, numbered 800-50. Which from herein will be NIST SP800-50. Or SP800-50. Or ‘that damn paper.’ And in SP800-50 they defined the elements necessary for a good security awareness program.

First, they defined awareness. And since they largely came from an academic and technical background, they saw ‘Awareness’ as belonging to the learning space; so they asked learning developers. ‘Awareness,’ as defined by NIST, goes along with ‘Training’ and ‘Education’ as three different aspects of learning. It inherently includes behavior change because we all thought people were rational and assumed that as soon as they were aware of a risk, they’d do something about it. ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’ by Daniel Kahneman put the last nail in that particular rationalist coffin.

Jump forward 20 years to the mid-2010’s and many people (myself included) were using the phrase ‘Awareness is not enough!’ We thought we should also be looking at behavior change, and then cultural change, to really impact our organizations.

Someone at NIST is saying “yes, we said that!”

Sadly, no one really listened to them.

Then, the field matured: not just awareness, but security more widely, and we all realized that cybersecurity’s role is to reduce risk for the business, not just protect things. Which meant that awareness, behavior change, and cultural change should all be risk related. More specifically, human risk related.

Which now makes us Human Risk Managers. Maybe.

Why Names Matter

Names are really important.

They’re one of the things that define us as humans. We’re a classifying species (as a trained librarian, of course I would say that). There are whole heaps of stories where knowing someone’s true name gives you power over them.

When we discuss what we are called as a profession, it matters. If you’re job seeking, how do you search for roles? That’s where Security Awareness has the benefit of history and familiarity, but also suffers from an image problem. Many people see Awareness as that stereotypical ‘mandatory e-learning’ or ‘Computer Based Training’ that happens once a year and doesn’t make a difference.

Cybersecurity Human Risk Management isn’t Security Awareness 2.0. It’s looking to do something different.

So, what is that?

Human Risk Management or Security Awareness?

There’s a lot of people, especially vendors, trying to tell you that they’re doing Cybersecurity Human Risk Management. And that’s fine. They’ve got a product to sell that hopefully fixes problems and creates value. If you talk to enough of them, as I have, you’ll start to see the commonalities in what they’re talking about.

Here’s what I’ve learned, and how I define Human Risk Management (HRM):

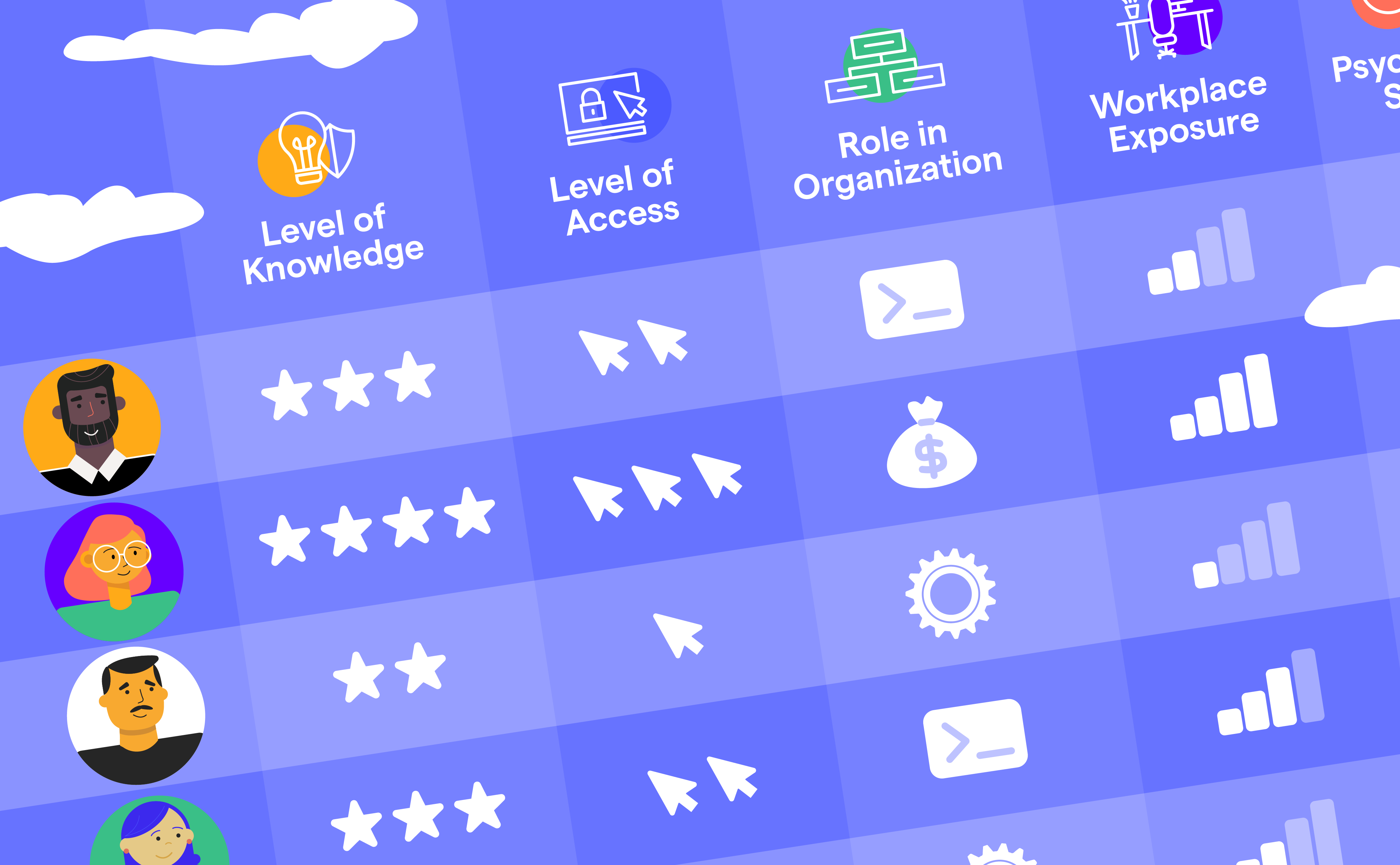

- Data, not guesswork: ‘Awareness’ is a broad-brush tool – we look at past incidents and try and learn from them. As much as possible, HRM looks at real work data – it uses information from a variety of sources to monitor and track your colleagues in as near to real time as possible. It might look at Teams, Slack, Secure Mail Gateways, SharePoint – anywhere where people are using data or communicating.

- Actions, not beliefs: people’s beliefs, attitudes, and values about security can be a massive driver of your organization’s security culture. But they’re not directly part of human risk management, they feed into it. HRM looks at what actually happened. To a certain extent, it doesn’t matter why someone clicked on a link or misconfigured a cloud service. What matters is that they did. Because now you have a problem to solve.

- Specific, not widespread: Human Risk Management should using the data of behaviors to target and support the people who need it, not bothering the people who are making secure decisions, and behaving appropriately. Let them get on with it (but maybe use them as good examples).

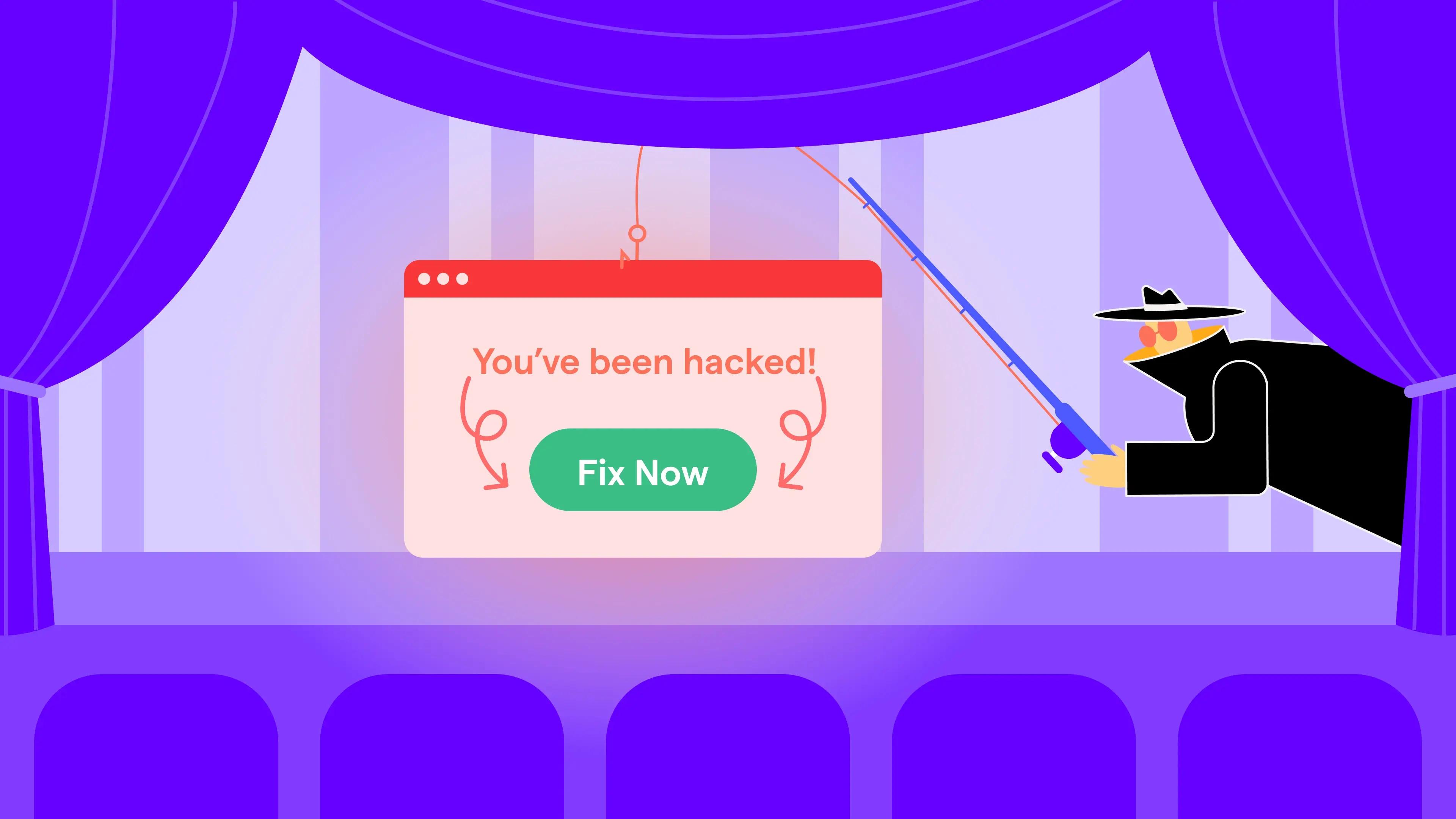

- Fix first, train later: When the house is on fire, lectures about fire safety are less important than doing something, even if it’s just phoning the fire brigade. So HRM is about doing something. That might be firing off an alert to your security team or using IDAM systems to lock down risky files with PII in them.

Training is important, don’t get me wrong. But it’s not a silver bullet that prevents people from committing errors. Even highly trained people get it wrong. - Actionable feedback: I once fell for two phishing simulations in a row. But what was really useful was that the feedback I got was personal to me and actionable. It told me that my personal risk profile was basically ‘reading emails on the train in the morning’ and that’s exactly when I missed that they were both phishes. Now I know to focus more when I’m commuting in (and not read emails before coffee).

- More than phishing: We know that phishing (and all the other related social engineering ‘ishings’) is still the main threat vector for cyber criminals and fraudsters. But it’s not the only risk that our organizations face, and that means that HRM needs to look at other areas where we interact with technology, might make mistakes, or be susceptible to cyber criminals.

HRM as an Approach, Not Product

As a concept rather than a product, Human Risk Management is a way to help us hone in on the inevitable errors that people commit without putting more pressure on them. And doing so without annoying or inconveniencing the people who are already doing the right thing.

It’s not about making everyone care about security, it’s about supporting them in making the right decisions when needed and fixing the problems that need fixing as quickly as possible.

Working With the Human Factor in Cyber

‘Human error’ is a lazy response. If someone tells you that they’ve looked into an incident and the root cause was ‘human error,’ laugh at them. Human error is inevitable. Decades of research tell us that. Having humans in a system is an inherent risk.

But let’s be very clear about a few points to conclude:

- Humans are why the systems exist. There isn’t an organization in the world that wasn’t built by people, for people. And we give people choices to make deliberately: to use their skill, judgement, and discernment to give us the best outcome. Sometimes, that means they’ll get it wrong.

- All humans commit errors. That means you, security team. You’re not immune.

- We don’t expect perfection from any other layer in our defenses. Why do we expect it of our end users? Any phishing email in my inbox has beaten all of your technical defenses. So why is it my fault if I click?

- Human risk management shows us where risk exists in our organizations and give us the tools to reduce that risk. It’s not about blame, it’s about helping our people be safe, and letting them get on with their lives and their work.

Life is risky by nature. Let’s help our humans manage it.