The Misaligned Incentives of Cybersecurity : Lessons from Healthcare

Nov 26

Get in touch with our HRM Specialists

Introduction

These topics are dear to my heart, and I am striving in my career to solve them as much as I can in alignment with the stakeholders’ objectives and concerns. To illustrate this, let us dive into the similarities between the U.S. healthcare system and the cybersecurity practices I have observed over the last two decades.

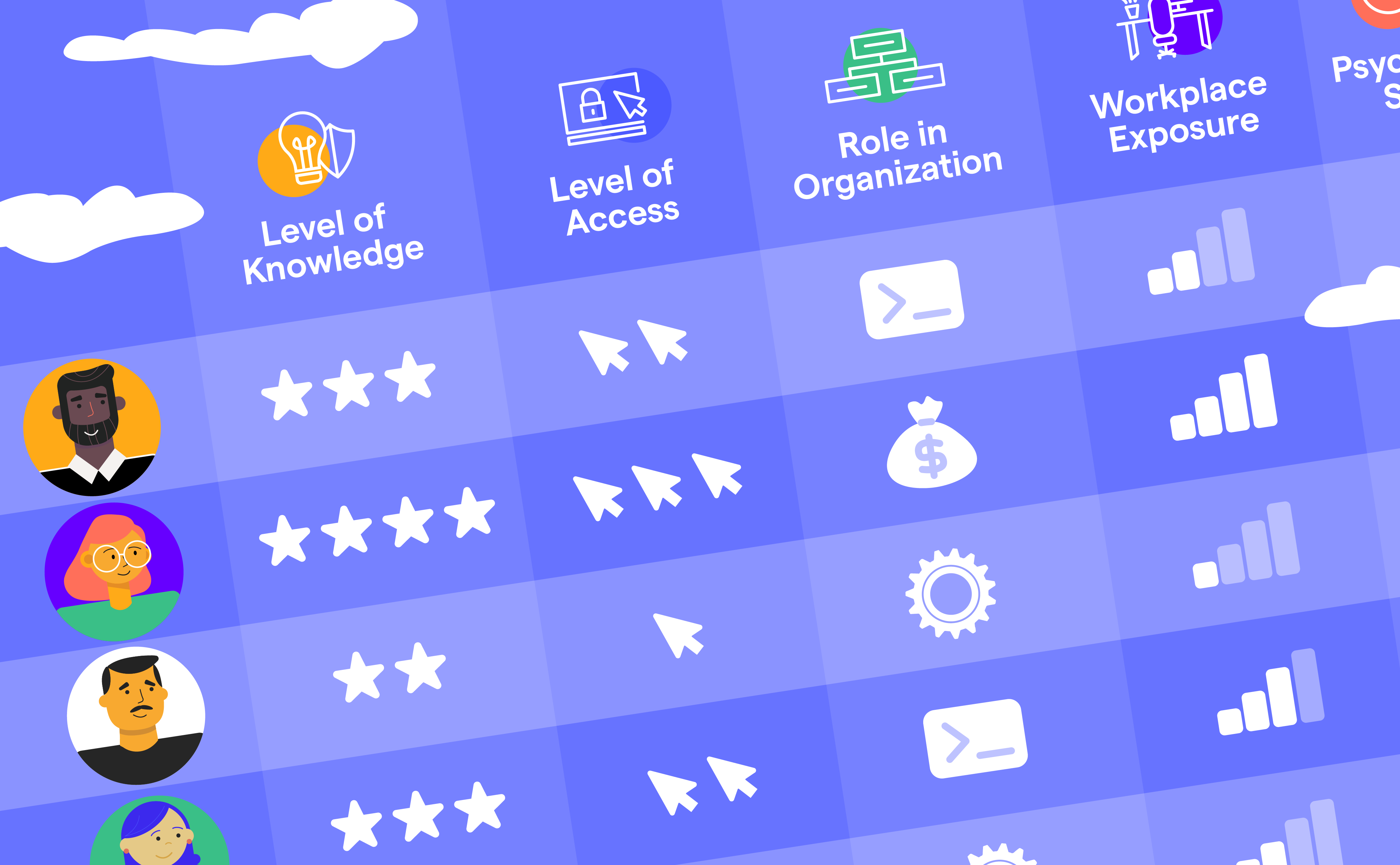

This experience has reinforced my conviction that agreeing with all stakeholders on what “good” looks like is the most important step toward achieving a target state. The tactics and methods may differ, but without a shared understanding of the objective, most efforts become futile. Even in collaborative environments, goals can differ significantly depending on the value systems of the participating groups. A strong corporate culture with tangible mission statements can help, but outcome-oriented cybersecurity still requires a clear, transparent articulation of what is to be achieved. Only then can motivation and incentives shape the path toward measurable progress.

Why Incentives Matter

The challenges we face in cybersecurity are not necessarily new, even with the rise of AI. At their core, these remain human dynamics - questions of alignment, incentives, and power. Until AI agents act with self-directed consciousness, they will continue to reflect human intentions. Even if they eventually operate independently, they will still mirror familiar social and geopolitical power dynamics - not entirely new, but difficult to manage.

In that sense, autonomous AI processes represent “human equivalents” with their own objectives and value systems. If not aligned with human goals, they may pursue outcomes guided by a different interpretation of what is “good” or “bad.” This is not unlike how organizations often misalign internally - where departments pursue goals that conflict with one another despite sharing a common mission.

The Healthcare Analogy

A good analogy for the challenges in cybersecurity is the healthcare system. Other parallels may exist in education or public infrastructure, but healthcare provides a particularly tangible comparison with layered incentives and measurable outcomes.

A well-functioning healthcare system should increase the health and resilience of its clients. It should motivate behavior that prevents future issues and strives for better long-term outcomes. In practice, that means encouraging healthy lifestyles and preventive care — exercise, good nutrition, and mental well-being.

At a minimum, such a system should be able to define its mission in outcome-oriented terms: for example, “maximize quality life expectancy over cost per individual.” The cheaper each additional year of healthy life, the more successful the system. But parameters must be agreed upon carefully — an over-optimized metric could produce unintended results, such as a “cheap” life expectancy of only 28 years.

If we accept this logic, a physician should encourage patients to reduce dependence on medication by addressing root causes through healthier behavior. That mindset — measuring success by patient improvement rather than treatment volume — would lower collective healthcare costs for all.

Yet this approach requires a complete reset of incentive structures. Today, healthcare providers are often rewarded for the volume of care delivered rather than its effectiveness. Talking customers out of consuming products is, by current logic, bad for business.

However, if the success of each physician were measured by the health improvement of their patients, incentives would align. Similarly, patients might receive discounts or face penalties based on how well they follow health recommendations — with exceptions for high-risk situations like certain sports.

In essence, accountability and outcome-based metrics would drive behavior change. Just as reckless drivers lose their licenses, individuals ignoring agreed-upon safety norms would bear consequences — not to exclude them from society, but to redirect their choices.

From Healthcare to Cybersecurity

Cybersecurity faces the same problem of misaligned incentives. Information security teams are rarely measured by outcome-oriented targets such as reduction in incidents or cost of breaches prevented. Instead, they are assessed on how well they manage budgets, tools, and headcount.

Leaders often showcase progress by acquiring new tools — expanding portfolios that increase complexity and cost — rather than demonstrating tangible improvements in resilience. Success becomes defined by activity, not impact.

A simple example: one vendor might be replaced by another after “efficiency gains,” but the total spend remains or even increases. Or a new tool is added without retiring older, redundant ones — leading to integration challenges and hidden maintenance costs. The result is a perception of improvement without a measurable outcome, a kind of “Pling-Factor” success that looks good on paper but does not advance the real mission.

Another provocative example: many security teams avoid discussing with boards whether every employee truly needs unrestricted access to the external internet. Instead, they defend inflated budgets to mitigate risks created by those very freedoms. It’s a multi-million-dollar annual cost driven by reluctance to enforce boundaries — even though providing separate personal-use devices could be cheaper and safer.

This brings us full circle to the earlier point: without a shared definition of success and aligned incentives, even good-faith efforts can work against the larger mission.

Conclusion

Like healthcare, cybersecurity is burdened by structural misalignments. True progress requires transparent articulation of goals, clear accountability, and incentive systems that reward real outcomes — not activity for its own sake. Only when we collectively define what “healthy” looks like for our digital ecosystem can we begin to build resilience that is both effective and sustainable.