Executive Summary

Cybercriminals have been utilizing emails to phish their victims for 30 years without notable reductions in breaches.

Despite many organizations now employing technical solutions to help limit the number of phishing emails landing in employees' inboxes, continual changes in cybercriminal strategy have left the number of phishing breaches largely defense. Employees continue to be the ultimate phishing combatant due to current limitations in technology, yet their own constraints are often misunderstood. Organizations are now applying more focus to human-based interventions. However, more needs to be done with regard to what an employee requires to become competent, motivated, and feel socially empowered to help protect their organization. While discussions around this topic reach far wider than the scope of this report, a number of important factors are considered around how organizations can better manage human risk in relation to phishing, and what should be expected of any intervention tools organizations choose to employ. Current success barriers for both educational and ‘in-the-wild’ phishing interventions are discussed, alongside solutions indicative of OutThink that work to overcome these challenges.

To mitigate human risk in phishing, organizations (and the tools they choose to employ) must offer interventions that work within human cognitive constraints while considering all aspects that can influence behavior. Security awareness training interventions should offer training focused around motivational and cultural aspects of behavior, as well as the more technical competencies usually assigned. Any competency-based training should support the full range of human decision-making modes by reinforcing new, habit-forming cognitive strategies applicable to heuristic processing. Phishing simulation tools should offer further ‘in-the-wild’ training that focuses on the application of these new cognitive strategies. These tools should have the ability to target organization risk hotspots as well as current phishing trends to ensure the effective application of company time and budget. Finally, phishing simulation tools should actively collect feedback from users as phishing training campaigns are conducted to avoid feelings of anger and victimization among employees.

To maximize its effectiveness, employee phishing training must account for the organization's industry, the main phishing risks affecting it, employee role, current phishing trends, and their level of phishing resilience. Employee psychographic profiles should also be considered to ensure that phishing training is tailored to specific vulnerabilities.

Security awareness training must consider motivational and social factors, as well as standard competency training. Employees need to not only have the required skills to protect themselves and their organization, but also feel motivated and supported to implement those skills in the workplace.

The primary focus of phishing simulation tools should be to provide 'in-the-wild' education, post security awareness training. Simulations should offer further embedded education that supports habitual phishing detection while reporting on current organizational risk hotspots.

Phishing simulation tools should offer a range of highly targeted email templates that can support an organization’s phishing risk strategy. Simulations sent to employees should be focused around current organizational risk areas as well as key phishing trends.

Employees often experience feelings of anger and victimization after a simulation. Organizations and simulation tools should consider employees active researchers that help highlight current risk areas and encourage them to provide feedback to inform future simulations.

Chapter 1: Phishing in Context

1.1 The Internet

Since the advent of mainstream internet services during the early 1990s, revolutionary developments emerged across areas such as communication, eCommerce, entertainment and information sourcing. However, alongside these developments, decreases in privacy and increases in opportunities for theft have also arisen. Despite these concerns, the internet has become integrated into every aspect of human life, making it impossible to imagine a world without it.

1.2 First Phish

From the inception of ‘internet for the masses’, cybercriminals worked quickly to develop ways to manipulate the service to their benefit. This began early on with the formulation of an algorithm created by a community known as the Warez group, generating random credit card numbers to allow the creation of bogus America Online (AoL) accounts. Despite AoL putting a stop to the algorithm using new security provisions, the hacking community quickly changed tactic, moving instead to impersonation. Hackers would utilize AoL and later AIL email and instant messenger to communicate to customers under the guise of an employee, requesting account and billing verification. In the end, AoL were left with no other option but to warn their customers against revealing personal information on their platform. That warning remains current for email and internet services to this day.

1.3 Phishing Continued

The emergence and growth of eCommerce only exacerbated this situation with the first documented (but unsuccessful) eCommerce attack taking place in June 2001, targeting the E-gold online payment system. Later that year, a successful phishing attack occurred using the subject of a 9/11 ID check around the attacks on the World Trade Center. In September 2024, cybercriminals then took their next step by registering numerous website domains similar to those of companies such as eBay, Yahoo and PayPal. These emails included links that would direct people to spoofed websites where they were asked to enter their personal information. Since then, the use of emails to source user information, download malware, and achieve financial gain has not abated. In 2021, phishing remained one of the top threat actions utilized by cybercriminals and approximately 83% of organizations experienced a phishing attack (Cybertalk, 2022; Verizon, 2022). Over time, phishing has become more targeted (spear phishing), focused on those possessing highly sensitive information (whaling), and has continued to leverage global devastation, as demonstrated by the the Covid-19 pandemic.

Even 30 years after their inception, phishing emails still remain one of the top threat actions responsible for cybersecurity breaches.

Chapter 2: Human Risk in Phishing

Across the globe, developers have continued to advance technologies that help identify phishing emails prior to them landing in employee inboxes.

Most companies now utilize email filters to minimize employee exposure, but attackers continue to find increasingly sophisticated ways of bypassing these filters with employees left making the decision on whether a communication is malicious. Once bypassed, cybercriminals employ social engineering strategies to subtly manipulate recipients into responding to emails in a desired manner. The weapons of influence used in phishing emails account for a large portion of why humans are estimated to be at the root of 82% of cybersecurity breaches (Verizon, 2021).

2.1 Human Limitations

As humans, we live in a world where simultaneous decisions need to be made at any given time, yet we only have the ability to fully process a small number of them. We therefore have to use previously acquired rules of thumb in around 95% of these decisions, saving cognitive energy for those we deem more important (Kahneman, 2011; Bargh et al., 2001). This quick but less rational way of thinking has its benefits but can often result in a decision less optimal than if conscious thought had been applied. Social engineers are aware of this and construct emails with the purpose of encouraging quick thinking, as they know that processing the email more consciously may result in the uncovering of clues that will expose the communication as malicious.

2.2 Offender Strategies

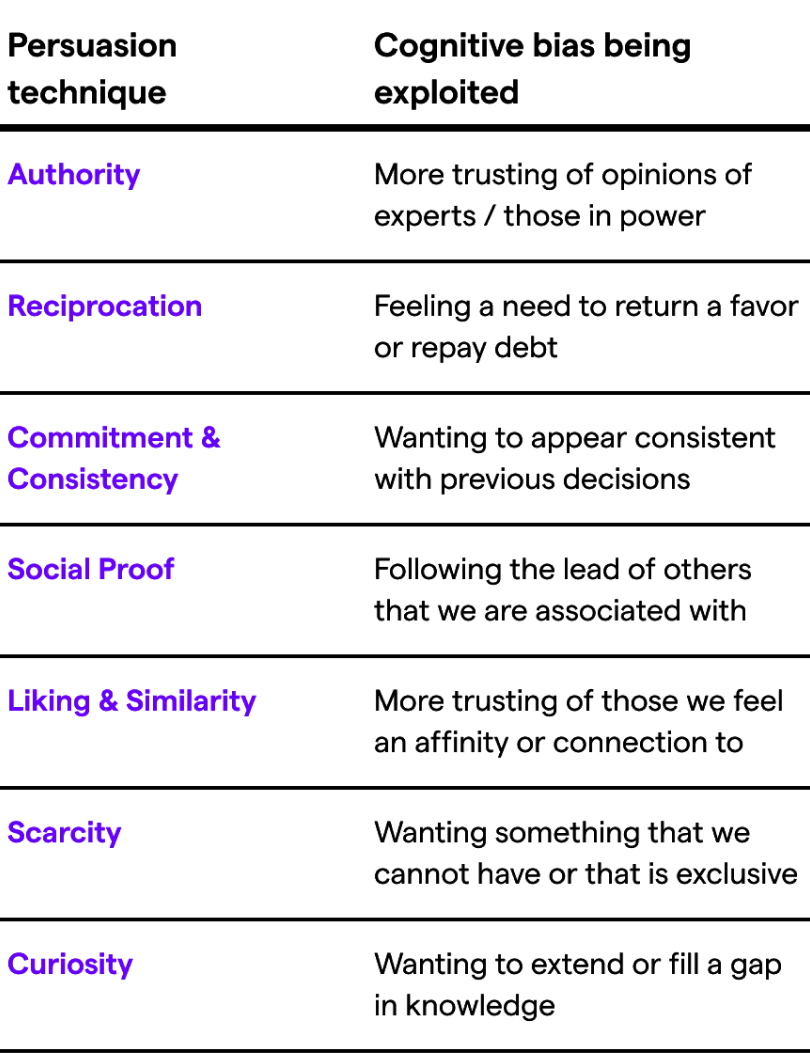

When the psychologist Cialdini published his book detailing his research on the top methods of persuasion used by salespeople and marketeers in 1984, email phishing was not considered a social engineering concern. Fast forward a decade and these strategies (among others) were being used by cybercriminals to maximize the effectiveness of their deceptions the moment a recipient opens an email.

Considering these techniques in relation to phishing emails:

Could be triggered in an email by the offer of a ‘free gift’ or ‘discount’ alongside a suggestion that the recipient click on a link to complete a survey.

Will often be used by identifying the recipient as a customer, reader or someone who has previously donated to a good cause in the hope that they will feel inclined to respond with interest again.

Could be a statement such as ‘80% of your colleagues have already completed the survey – please follow the link below’, thus providing a social basis for fast-tracking decision-making.

Attempts to build rapport, offer praise or suggest a common interest.

Can be presented in phishing emails via terms such as ‘for a limited time only’ or ‘exclusive deal’ to encourage a quick response.

Exploits the human need to fill gaps in knowledge and can present as a simple link or part of a story with a need to click outside of the email to learn more.

These weapons of influence can be laced into phishing emails – often in combination – to promote heuristic decision-making and detract from recipient attentiveness. Once cybercriminals have initiated intuitive decision-making in the recipient, they will then suggest an action to capitalize on their reduced vigilance. The threat action most likely to be included in a phishing email is a malicious link (around 70% of phishing emails), possibly numerous links in the hope that at the very least the recipient will click ‘unsubscribe’. Other threat actions can include replying to an email with personal details, opening an attachment, downloading software or completing a form. Cybercriminals use an arsenal of psychological manipulation tools to enhance their deceptions. For example, 38% of phishing emails include imagery concealing malicious links knowing full well that humans will attend to these images before even reading the text (Matz, Segalin & Muller, 2019).

Cybercriminals are trained social engineers. They will ensure phishing emails are peppered with numerous psychological tactics to push recipients into quick decision-making in the hope that they will perform the suggested threat action prior to uncovering clues to detect its true motive. It is therefore illogical to expect employees to always think rationally when interacting with emails, and fully apply the lessons of security awareness training. Any security awareness training program should consider how their content supports users in detecting malicious communications even when in heuristic decision-making mode.

Cybercriminals are aware of human cognitive limitations and utilize them to their benefit. Phishing training must reflect how cybercriminals manipulate cognitive constraints and provide guidance on how to recognize them.

Chapter 3: Human Risk Management for Phishing

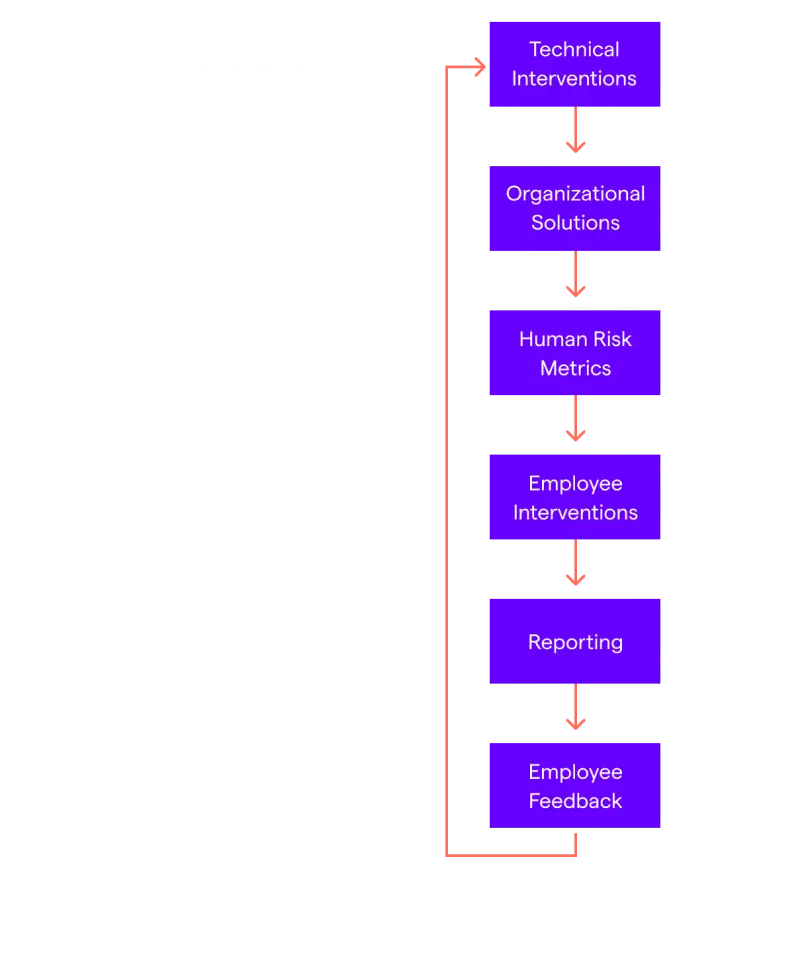

Many interventions currently deployed to manage human risk in phishing don't fully account for human cognitive limitations nor support employees outside of conventional training. Calibrating appropriate expectations for employees and tailoring phishing training solutions accordingly are essential to safeguarding any organization. A comprehensive human risk management approach should answer the following questions:

- What technical solutions reduce as much risk as possible before it reaches employees?

- Once satisfactory technical solutions are implemented, how can organizations facilitate secure employee decision-making regarding phishing?

- What are realistic expectations of employees considering human cognitive constraints, their roles, and the nature of the business?

- What are the bests ways to effectively segment any higher risk groups/areas?

- When targeting these groups, how can findings from psychological research, industry knowledge and employee experience inform the most effective solutions?

- How are human risk factors measured to gauge training success over time?

- How is user feedback leveraged to optimize technical, organizational and employee solutions for continuous improvement?

3.1 Adaptive Security Awareness Training for Phishing

3.1.1. Current challenges

Recently, views around the human's role in guarding against cyber-attacks have become more affirmative. Organizations are now being asked to view their employees as valuable shields as opposed to easy entry points for a potential breach. Cybersecurity budgets are invested, specialist roles assigned, and time allocated to educate employees around detecting phishing attacks. Despite these investments, phishing emails remain one of the top threat vectors responsible for cybersecurity breaches (Verizon, 2022).

Cybersecurity interventions' lack of success is attributed to a number of factors, including excessively technical content, poor knowledge transferability, and poorly scoped training (Bada, Sasse & Nurse, 2019; Alshaikh et al., 2018; Skinner at al., 2018, April 2018; Scholl, Fuhrmann & Scholl, 2018). Employees are often too busy to apply their knowledge or pay attention to a secondary task and perceive cybersecurity as a burden (Pfleeger & Caputo, 2012).

Other challenges cited include institutional barriers such as insufficient government support, business-related budget constraints, personnel challenges such as individual employee differences, and work-based pressures (Aldawood et al., 2019). These findings suggest that awareness and intervention tools would benefit from drilling down on higher priority phishing risk areas so that phishing awareness training is better targeted to individual needs and time and budget allocations are optimized.

Another reason phishing training often fails to translate to real-life reductions in phishing success rates is its erroneous assumption that employees are constantly applying analytical thinking to screening their emails. Humans are estimated to make 95% of their decisions unconsciously, which clearly suggests the need to go beyond what conventional phishing training offers. Not only do employees need education, they also need concrete guidance and practical strategies specific to opening emails in heuristic decision-making mode. (Croskerry, 2013; Larrick, 2004; Arkes, 1991).

Many security awareness training programs assume humans process emails analytically despite the fact that 95% of decisions are made intuitively. To be effective, phishing training must address 100% of human decision-making modes.

3.1.2 Solution

Since humans process the majority of their decisions unconsciously, it's unrealistic to expect employees to recall all of their training every time they open an email. Practically speaking, employees are often multi-tasking and working under pressure - they don't have the bandwidth to constantly bring their full phishing education to bear.

While conventional phishing training remains an important aspect of security awareness training for employees, it must be augmented with new, habit-forming cognitive strategies compatible with intuitive decision-making.

Humans often create their own strategies to reduce unconscious error, like leaving their car keys in the same place to avoid losing them, for example. Similarly, employees tend to develop comparable behavioral strategies on their own to facilitate engaging in secure behavior at work (Vishwanath, Harrison & Ng, 2018). Security awareness training should therefore focus on stimulating the development of easily adopted heuristic strategies aligned with the desired security outcomes.

Cognitive strategies that can be used to support intuitive decision-making include 'consider the opposite' (where it's assumed each email is a phishing attack and users screen for clues that invalidate that assumption) or the use of simple maxims such as "measure twice, cut once" common in carpentry (Croskerry, Singhal & Mamede, 2013).

Phishing training must go beyond conventional education to instill phishing detection strategies compatible with heuristic decision-making.

Go Beyond Phishing Competency

Security awareness training should not be based solely on building competency. Training employees on the skills required to check if a link is malicious, or detect a bogus sender email address is important, but competency alone doesn't guarantee employees apply their knowledge when needed. Though many employees possess the requisite skills, they don't necessarily implement them. Employees may not do so for several reasons:

- Perception of low risk probability

- Perception that a secure behavior isn't important

- Control friction I.E. additional time spent complying with a secure behavior

- Cybersecurity culture I.E. the emphasis on the importance of cybersecurity in an organization

(Thomas, 2018; Fogg 2009; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Ajzen, 1991; Rogers 1975)

If employees don't regard cybersecurity as critical in their organization, then they are less likely to implement the skills they learned through their phishing training.

In addition to the cultivation of employee motivation and the requisite skillset to protect themselves and their organization against phishing attacks, motivation and behavior change models also emphasize peer influence and a sense of community. (Ryan & Deci, 2020, Rogers, 1975). Phishing training should therefore be integrated into a cybersecurity awareness culture centered around knowledge sharing. Knowledge sharing involves a bi-lateral exchange of ideas - the provision and receipt of information (Shaari, Rahman & Rajab, 2014). Employees should be provided the opportunity to identify and address gaps in their knowledge, flag those recognized in their colleagues, and point out holes in security policy and security awareness training to ensure cybersecurity awareness is continually optimized. Security awareness training tools should facilitate these practices by providing employees the opportunity to submit feedback on knowledge gaps they've experienced or observed.

Security awareness training should go beyond just a library of training modules to promote motivational and cultural factors that enhance cybersecurity culture.

Drill Down on Critical Cyber Risk Areas

It’s not about quantity when it comes to delivering awareness training, but quality. Humans are limited in the amount of information they can ingest as well as the time they are willing to put aside to do so. Providing employees with large numbers of irrelevant training modules that don't apply to their regular working environment diminishes motivation and knowledge recall. (Scholl, Fuhrmann & Scholl, 2018).

While a number of modules will be appropriate for the entire workforce, subsequent training needs to be allocated through effective segmentation. Those working with payment card data, employees exhibiting low knowledge and engagement, and users in senior management (to name just a few of many segments) should receive training relevant to their psychographic profile and function.

In addition to employee limitations, organizations are often restricted in the amount of time and budget they can allocate to cybersecurity awareness training.

This makes it all the more important that security awareness training platforms use appropriate, human-centered metrics that highlight key risk areas for each employee and automatically formulate individually tailored training programs to remediate them. By ensuring every user receives only those modules related to the risks they present because of their work, behaviors, and psychographic profile, organizations can enhance their security while reducing employee cognitive load and time and budget costs.

Security awareness training platforms need to effectively drill down on key risk areas to enhance phishing risk mitigation and optimize employee and organizational resources.

3.2 Phishing Simulation Tools

3.2.1. Current challenges

A number of phishing interventions have been formulated outside of standard educational practices with offerings such as cybersecurity rule books and gamified learning. Increasingly popular phishing simulation tools have the potential to train employees using novel cognitive strategies. Phishing simulations involve sending employees mock phishing emails that mimic phishing content and evaluate how employees react to them 'in-the-wild.' The objective performance metrics generated by these true-to-life phishing simulations enable organizations to benchmark security awareness training effectiveness.

That being said, phishing simulations are often exclusively used as a compliance and reporting tool without any consideration for embedding real-time education to maximize employee learning. Surface-level metrics such as links clicked, files downloaded, and credentials captured are often used without providing any window into understanding the contextual situation or social engineering technique that caused the individual to fall for the phishing simulation. There are also potential legal and ethical concerns arising from the possibility that employees feel victimized and angry after being phished by their own organization. (Rizzoni et al., 2022; Finn & Jakobsson, 2007).

While phishing simulation tools have the potential to offer useful ‘in-the-wild’ training, they are viewed largely as a reporting tool with employees left feeling angry and victimized.

3.2.2 Solution

Often, phishing simulation tools are used to assess organizational phishing resilience through metrics such as click and credential capture rates. These tools should also be deployed as vectors for employees to practice the skills imparted by security awareness training and build the habits to intuitively detective malicious communications in real-world settings.

At minimum, phishing simulations should include embedded training which teaches employees new detection techniques in context and in real time right after they interacted with a phishing simulation email and are already engaged. (Yeoh et al., 2021).

Phishing training should include information on how cybercriminals prey on human cognitive limitations, how to discern situational clues stemming from these techniques, how to detect red flags suggestive of malicious communications, and how to respond when a phishing email is detected. In this sense, phishing simulation statistics reporting should be viewed as phishing simulation tools' second benefit that helps organizations refine subsequent phishing simulations and inform security awareness training campaigns.

Phishing simulations should serve as an educational tool that measure real-time human risk and provide direction for future phishing training.

Targeted and Relevant Phishing Simulation Campaigns

Phishing simulation email templates often replicate recently identified phishing emails and are periodically sent out to all employees in blanket fashion. Phishing simulation tools should also utilize targeted emails and embedded training to enhance educational practices and optimize reporting. (Rizzoni et al., 2022).

At minimum, phishing simulation tools should offer a range of difficulty settings to ensure that phishing emails challenge employees, nurture a sense of mastery, and address perceptions of unfairness. They should also segment and filter for type of industry, job role, and the associated likely pretexts that mimic what well-targeted phishing emails would look like in the real world. (Yeoh et al., 2021).

The ability to vary and tailor persuasion and social engineering techniques according to cybercriminals' current practices will also further optimize the instructional effectiveness of phishing simulations (Pirocca et al., 2020; Oliveira et al., 2017). Phishing email template variations in sender location (internal or external), threat actions such as links, attachments, or ransomware, and attack motives reflective of evolving trends also enhance phishing resilience and risk mitigation.

A library of phishing email templates designed to enable such modulations helps an organization paint a richer picture of their cybersecurity human risk profile. For example, the 'authority' persuasion technique is more deceptive when it appears to come from a source within the same organization. This insight, in turn, can be leveraged for targeted training or interventions like changing communication patterns between executives and employees within the business.

In addition to generic phishing simulation templates, more targeted phishing training campaigns reflecting current organizational risk and phishing trends should be employed.

Employees as Researchers, Educators, and Informants

Employees that have been phished through simulations instigated by their organization will often be left with feelings of anger and victimization (Rizzoni et al., 2022; Finn & Jakobsson, 2007). It is therefore important that employees' role as researchers is emphasized and highlights the importance of understanding how current phishing trends are impacting their organization. Social engineers are highly skilled at targeting any potential cognitive weaknesses in humans, meaning anyone is vulnerable to the tactics they resort to.

Employees must feel legitimized in the role they play in supporting their organizations in mitigating phishing risk and developing forward-looking phishing risk strategy through phishing simulations, whether they clicked on a link or not. Phishing simulation tools should always enable employees to provide feedback about their conscious thought processes, which device they were using when they opened the email, their appraisal of the embedded training, and their understanding of current phishing trends. Upon completion of their phishing simulation training, employees should see clear value in the instruction and feel more competent in detecting malicious communications moving forward.

Communication around phishing simulations should aim to reduce feelings of frustration and victimization in employees and highlight their contributions to protecting their organization against future phishing attacks.

Conclusion

Cybercriminals have been using phishing emails to phish their victims for 30 years without any significant reduction in the number of breaches organizations suffer.

Despite the introduction of numerous technical solutions designed to guard against phishing emails, cybercriminals continue finding increasingly sophisticated ways of bypassing them. Employees are still held responsible when phishing attacks succeed without due consideration for their limitations or support tailored to their constraints when faced with malicious communications.

Humans make around 95% of decisions intuitively, yet training solutions largely focus on employees processing emails consciously. Phishing awareness training should provide employees with alternative, habit-forming cognitive strategies that support the full range of human decision-making modes. Security awareness training modules must also consider motivational and social factors alongside standard competency training to emphasize the importance of implementing the phishing simulation tools and strategies to employees. Any phishing awareness training platform must use metrics that enable organizations to focus on key risk areas both for individuals and groups. Doing so focuses company time, budget costs, and employee cognitive load on the highest risk areas affecting the organization.

Phishing simulations should be deployed to complement security awareness training with 'in-the-wild' training that incorporates embedded instruction to improve phishing detection. This phishing training should be highly targeted and focus on the organization's phishing risk strategy and the latest phishing trends used by cybercriminals. Communication around phishing simulations should underscore employees' role as active participants in ensuring the embedded phishing training is relevant and provides clear value to safeguarding their organization.

References

OutThink’s data demonstrates that behaviorally segmented training, paired with actionable insights, is critical to improving cybersecurity engagement and reducing human risk.

By focusing on targeted nudges, adaptive training, and aligning security processes with business objectives, organizations can foster a security-first culture.

Ready to move beyond compliance and tackle human risk management at its core? Explore how OutThink’s CHRM platform can turn insights into strategies, driving measurable improvements in your organization’s security posture.